Does Hip Osteoarthritis Cause Pain in the Back of the Head

Osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a painful condition involving the deterioration of the cartilage inside your joints. Affecting 32 million people in the United States, it is the most common arthritic condition.* Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) is a world leader in the treatment and research of orthopedic and rheumatic conditions, embracing a philosophy of integrative nonsurgical and surgical care.

HSS is ranked #1 in the United States for orthopedics and #4 in rheumatology by U.S. News & World Report.

- What is osteoarthritis?

- What causes osteoarthritis?

- What is the difference between osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis?

- Which joints are most commonly affected by arthritis?

- What are the symptoms of osteoarthritis?

- How is osteoarthritis diagnosed?

- What tests are done for osteoarthritis?

- How is osteoarthritis treated?

- What are the nonsurgical options for treating osteoarthritis pain?

- When should I consider surgery?

What is osteoarthritis?

Osteoarthritis (OA), also known as degenerative joint disease, is the most common form of arthritis. It is a painful condition that occurs when cartilage inside a joint wears down over time. Most often, this wear results from a lifetime of use, and people get it when they reach age 50 or older. However, younger people may get the condition early as a result of an injury to the joint. Also known as post-traumatic arthritis, this form of osteoarthritis develops after an injury such as a fracture, dislocated shoulder or torn rotator cuff.

What causes osteoarthritis?

The use of a joint leads to wear and eventual degeneration of the cartilage that cover the bones where they meet in the joint. This loss of protective cartilage causes the joint inflammation known as osteoarthritis, as bone starts to rub directly against bone.

Cartilage is a smooth, spongy tissue that coats the ends of bones where they meet to form joints. In joints such as elbows, knees, shoulders, ankles and knuckles, cartilage acts as a shock absorber, cushioning the bones and preventing their ends from touching during body movement. This allows a person to twist, bend, turn and have a broad range of motion. The older we get, the more our cartilage deteriorates – especially in joints that we use most frequently. It is similar to the way brake pads in a car wear down over time. When cartilage degrades, the bones are not properly cushioned and the joint becomes damaged. This results in pain, stiffness and reduced range of motion.

What is the difference between osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis?

Osteoarthritis is a mechanical degeneration of a joint caused by use over time. Rheumatoid arthritis a form of inflammatory arthritis, which is a chronic disease of the immune system. Rheumatoid arthritis is less common than osteoarthritis but can often more serious and cause inflammation in many joints at the same time. Osteoarthritis, on the other hand, is usually isolated to individual joints such as the shoulder, or one or both hips.

Which joints are most commonly affected by arthritis?

Osteoarthritis is most common in large weightbearing joints such as the hips or knees. The joints most commonly affected by osteoarthritis are:

- the hips

- the knees

- the last and middle joint in the fingers

- the joint between the thumb and the wrist (basal joint arthritis)

- the neck (joints of the cervical spine)

- the lower back (joints of the lumbar spine)

What are the symptoms of osteoarthritis?

Pain is the most common symptom of OA, followed by stiffness. Pain usually increases during activity and decreases with rest. However, in the morning or after other long periods of inactivity, some people with OA may experience a feeling of stiffness. This symptom (known as "gel phenomenon" or "gelling phenomenon") is caused by a temporary thickening (or "gelling") of natural fluids inside the joint. It usually lasts for less than 20 minutes in the affected joint once a person begins moving again.

Pain felt during movement of the joint is often accompanied by a crackling or grinding sound called "crepitus." Some people with OA may feel little or no pain for unknown reasons. The level of pain each person with OA experiences can depend on many factors including: the stage of the disease, the way a person's brain processes pain messages, cultural, gender and psychological differences.

Osteoarthritis is not associated with the following symptoms. If you have these are symptoms, you have some form of inflammatory arthritis:

- swelling, redness or warmth in the joints where you feel pain

- fevers

- unexplained weight loss

- severe muscle atrophy (weakening)

- symptoms on both sides of the body (both knees or hips, etc.)

How is osteoarthritis diagnosed?

There are three key elements to getting an accurate diagnosis for osteoarthritis:

- a complete evaluation and physical examination by a doctor

- radiological examinations (X-rays and/or other imaging)

- laboratory tests

The physical examination

Your physician will talk with you to learn your medical history and symptoms, and then do a physical exam to assess:

- pain levels

- joint range of motion

- muscle strength in the affected region

- presence of any swelling or tenderness of the joint

- gait (the way you walk) if the disease is in the hip or knee

Radiological examinations

When the physical exam suggests a person may have osteoarthritis, different forms of imaging may be necessary to confirm the diagnosis and determine the severity of the joint degeneration.

Imaging for diagnosing advanced osteoarthritis

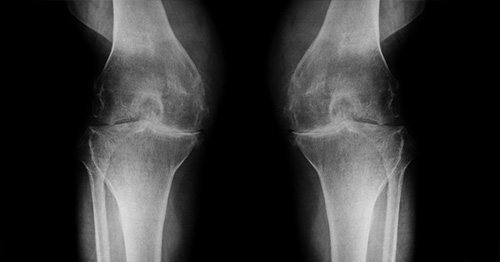

X-rays are very helpful in diagnosing advanced osteoarthritis because the affected joint will have specific characteristics:

- Bones that are closer to each other than they should be: As cartilage wears away, the joint space can narrow.

- Cysts: As the body responds to cartilage destruction and attempts to stabilize the joint, cysts or fluid-filled cavities can form in the bone.

- Increased bone density or uneven joints: When bones are no longer cushioned by cartilage, they can rub against one another, creating friction. The body responds by laying down more bone in response, increasing bone density. Increased bone creates uneven joint surfaces and osteophytes (bone spurs) around the joint margins.

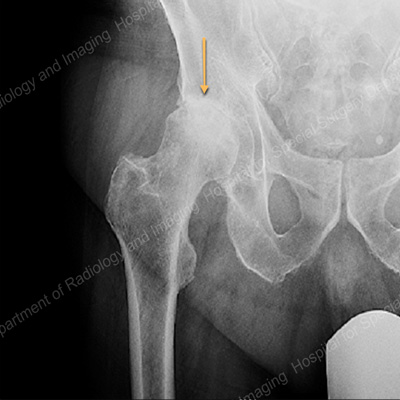

X-ray view of the hip joint showing osteoarthritis and joint space narrowing between the femur (thighbone) and pelvis.

X-ray view of the hip joint showing severe joint space narrowing and large osteophytes

Imaging for diagnosing early-stage osteoarthritis

Confirming early onset osteoarthritis is more complicated, because the signs are far more subtle. Hospital for Special Surgery has developed special X-ray views that increase the sensitivity of conventional X-rays, allowing detection of early changes in the joint before they are evident on routine X-rays.

In some cases, X-rays alone are not sufficient to show the smaller differences associated with early onset arthritis. When this is the case, other specialized diagnostic imaging technologies are used. These include:

- CT scan (computed tomography, sometimes called a "CAT scan"): A CT exam is excellent for showing the formation of osteophytes (bone spurs) and how they affect the surrounding soft tissues of the joint.

- Ultrasound: This sensitive imaging technology is useful for identifying synovial cysts that can form in association with osteoarthritis. Ultrasound can also be used to image articular cartilage in patients who cannot have an MRI exam because of certain medical conditions.

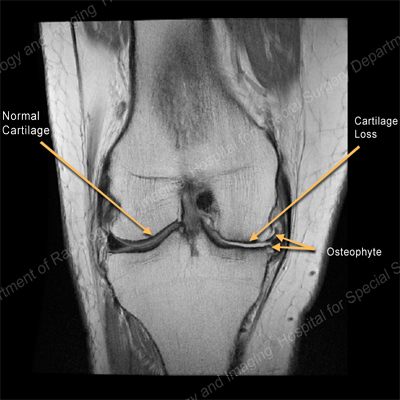

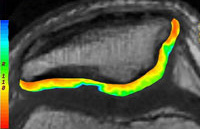

- MRI (magnetic resonance imaging): An MRI is very good at revealing subtle changes in both bony and soft tissues of the musculoskeletal system. MRI can demonstrate reactive bone edema or soft tissue swelling as well as small cartilage or bone fragments in the joint. At HSS, specific computer programs are used to identify early evidence of cartilage degeneration. When there is objective evidence of cartilage wear, appropriate treatment can be initiated to prevent or delay progression.

MRI of the knee showing normal cartilage on one side and cartilage loss and on osteophyte on the other

MRI of the hip demonstrating osteoarthritis with large osteophytes around the femoral head.

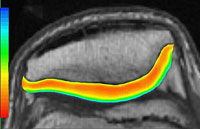

In some cases, when osteoarthritis is suspected, but X-rays appear normal, a special MRI process called quantitative T2 mapping can detect the subtle cartilage differences to confirm the diagnosis, as shown below.

Normal knee cartilage

Knee with osteoarthritis

What tests are done for osteoarthritis?

Laboratory tests are helpful for diagnosing OA, because they are used to rule out forms of inflammatory arthritis, such as rheumatoid arthritis. In other words, if you have joint pain and your lab results are normal, it would confirm a diagnosis of OA. These tests include:

- complete blood counts

- urinalysis

- sedimentation rate

- rheumatoid factor (to detect rheumatoid arthritis)

- antinuclear antibody (ANA) titer tests

When these tests return normal or negative results, this usually indicates that your arthritis is osteoarthritis. It should be noted, however, that as people age, they sometimes develop a low-level positive rheumatoid factor, ANA titer and/or elevated sedimentation rate without experiencing any obvious illness. This is why doctors do not rely on laboratory tests alone, but rather to confirm a suspected diagnosis for osteoarthritis.

Another lab test that may help confirm the diagnosis is the extraction and analysis of synovial fluid from the joint. Synovial fluid is a liquid normally found within the joints. It helps nourish and lubricate them and is usually present in only very small amounts. However, when certain forms of arthritis are present, synovial fluid will change.

In osteoarthritis, white blood cell count ("pus cells") is usually normal and the fluid is clear (like water). Higher white cell counts should suggest inflammatory arthritis or infection, rather than osteoarthritis. In this way, extracting synovial fluid can help to confirm the diagnosis. It can also reduce pain and swelling if the fluid is contributing to inflammation.

The fluid may also be examined for the presence of uric acid crystals (seen in gout) or calcium pyrophosphate crystals (seen in pseudogout or chondrocalcinosis). The measurement of other biological markers is still experimental.

How is osteoarthritis treated?

Your doctor will develop an individualized treatment program especially for you based on several factors, including:

- how severe your disease is

- which joints are affected

- the nature of your symptoms

- any other conditions you have and medications you take

- your age, occupation and everyday work activities

What are the nonsurgical options for treating osteoarthritis pain?

Whenever possible, early-stage osteoarthritis may be treated without surgery using physical and occupational therapy. NSAIDs (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) can often help, and corticosteroid injections may delay the need for surgery in some people. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) injections have been shown to benefit certain patients.

Oral medications

NSAIDs that may be used to treat osteoarthritis include ibuprofen (Advil), naproxen (Aleve) and celecoxib (Celebrex). Duloxetine (Cymbalta) is a medication used to treat anxiety and depression, but which has been shown to alleviate pain for a number of conditions, including OA. It is usually tried as a second medication option in osteoarthritis patients for whom NSAIDs have not provided relief.

Staying active is essential

For people with osteoarthritis, it is important to maintain an active lifestyle and avoid becoming sedentary. Movement can help reduce pain and prevent it from getting worse. But the appropriate and safe types of activity vary from patient to patient. As with any treatment, getting a proper "movement prescription" requires getting an accurate, pinpointed diagnosis and ensuring that all members of the healthcare team (orthopedists, physical therapists, etc.) understand each patient's unique condition.

To reduce the effects of early-stage knee arthritis, it is especially important to strengthen the thigh muscles to provide better support for the joint. It is also helpful to maintain good nutrition and a healthy weight. These measures will reduce the pressure on the knee joints to reduce knee pain and improve function. (Learn about the weight management program at HSS.)

When should I consider surgery?

When the conservative measures above are not enough and pain in a specific joint makes it difficult for you to move, then joint replacement surgery can restore your comfort and help you to return to normal activity. Hip replacement surgery and knee replacement surgery have become trusted treatments for restoring mobility and easing pain.

For cases of hip and knee arthritis, some patients may be able to have less invasive hip arthroscopy or knee arthroscopy procedures. Joint replacement surgery may also be an option for people with arthritis of the shoulder, elbow, wrist or ankle.

You are generally a good candidate for surgery if conservative treatment hasn't worked and you experience a significant interruption in some activity of daily life – for example, if you can't walk more than a city block or if you awaken from sleep with pain in the affected joint. In such cases, surgery should provide outstanding results, because you will become pain-free in the affected joint. The exact type of surgery you have will depend on your age, activity level, and the specific joint that is affected.

HSS research enhances arthritis treatment options

Hospital for Special Surgery's pace-setting medical research contributes essential knowledge to researching the prevention and treatment of osteoarthritis and inflammatory arthritis. HSS musculoskeletal medicine research is organized into five main programs:

- Arthritis and Tissue Degeneration Program: HSS investigations of the intricate cellular and molecular mechanisms of tissue destruction in all musculoskeletal conditions help reveal the cellular processes of cartilage loss in osteoarthritis. When a new important step of cellular interaction is discovered, it becomes a potential target for therapies that could prevent, slow, or even stop cartilage degeneration in OA.

- Autoimmunity and Inflammation Program: In-depth knowledge from HSS studies of how cells communicate and interact in inflammatory reactions in autoimmune diseases can be integrated with cellular studies of how inflammation is triggered – and then continues to impact – the joints in OA.

- Department of Biomechanics: The mechanics of the body's movement, function, and ability to carry weight are affected by every stage of osteoarthritis. Biomechanical research uses principles of engineering, materials science, physical and computer modeling, and advanced statistical analysis to study how OA impacts the body's function and gait. The department also continually researches innovations in the design and materials of joint replacements, surgical instrumentation, and orthopedic devices.

- Musculoskeletal Integrity Program: Using advanced technology not often available at one research center, HSS scientists unlock the understanding of the cellular nature of living bone: how it thrives, how it degenerates, how it interacts with soft tissue like cartilage and tendons, as well as orthopedic devices like implants.

- Tissue Engineering, Regeneration, and Repair Program: Cartilage does not heal itself. Yet, when injured, other soft tissues – like tendons and ligaments – can. Our ongoing studies of the cellular mechanisms of soft tissue degradation and regeneration can help uncover ways to slow and prevent cartilage loss. Understanding the cellular nature of soft tissues also informs the science of tissue engineering. Interdisciplinary studies at HSS are developing new biologic and synthetic tissues that can help damaged joints regain function and mobility.

References

Back in the Game patient stories

Does Hip Osteoarthritis Cause Pain in the Back of the Head

Source: https://www.hss.edu/condition-list_osteoarthritis.asp